Planning with Brain-Spaces

By Jonathan Lam on 06/15/18

Tagged: brain-dump

Previous post: Proof of Binet's Formula

Next post: The Wonders of PHP

I had this revelation in the shower that the brain acts like a very slow computer processor, with an arbitrarily defined number of cores (explained later). Each day, these cores can only process at a limited rate, and once a task is completed, the processing power devoted to it is freed up for another task.

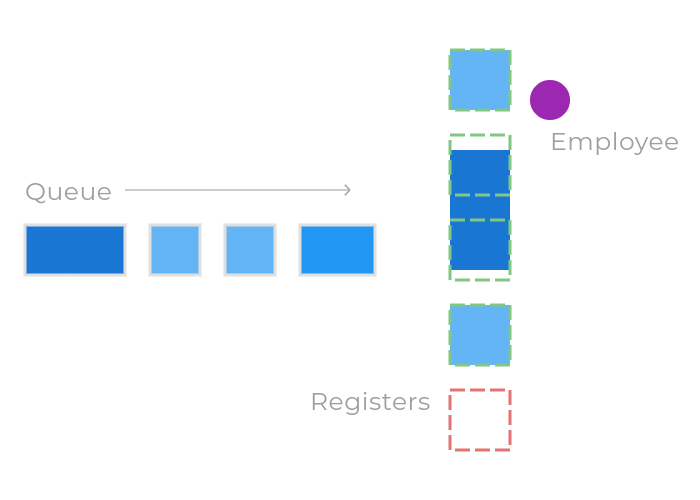

This may not seem like an important thought, but it was interesting to me. The main observation is a visualization of how much a person's brain can handle, on an average day. A good analogy would be a checkout line. There might be anywhere from two to five registers (the cores), and each register can only process a certain number of items a day. There are a few interesting points to consider, however:

- There is only one employee. He can decide to finish the work of one register at a time, or he can jump between the registers as he wishes.

- A high-priority customer can split up his shopping cart into multiple shopping carts, which can be spread over multiple registers, but this would require extra overhead and would tire the customer out from going back and forth repeatedly.

- If a customer has fewer than twenty items, another customer can use the register, but not without a long adjustment time (the registers are amazingly slow for modern shopping standards).

- Usually, one register is the "dozen items or fewer" lane, which also functions as a self-service lane (i.e., not requiring the single employee, and thus being able to run independently). This is usually kept open in case of emergency little purchases that need to be made, and is more prone to causing fatal technical problems than with the employee-operated regular registers. Depending on the type and urgency of the store's goods (e.g., imagine a pharmacy vs. a grocery store), there may be variable amounts of these emergency lanes, but it never takes up more than half of all the registers.

- At the end of the day, often there are still many customers in line, who often change their shopping carts' contents, and sometimes reconsider the act of purchasing and leave without purchasing anything. Only very rarely, for example during vacations, are there free registers (except the special one).

- While there is only one employee, the overall productivity of the checkout line (rate of items processed) increases as the numbers of registers increase, because each register machine carries out some of the technicalities the employee doesn't have to handle.

What an inefficient store! But when a person's brain operates at only a fraction of a FLOPS (as compared to the gigaFLOPS level of most modern processors) and handles both subjective, analytical tasks as well as objective, tedious ones, we have to slow down the pace quite a bit.

In this model, each register is one thought process; and, although everyday "multitasking" seems like a necessary skill for the average busy student or worker, life is often more along the lines of switching between tasks regularly. Personally, I think a person can only really keep track of between two to five major projects in their mind at once, and only really operate on one at a time (with the exception of the "emergency register," which will be explained later). The number of items that can be processed by each register is considered one "brain-space": an arbitrary value that might be in the value of calculations per hour per day. This unit is so strange because of the vague definition of each register: it is how much a person can perform on one topic per day, which is also dependent on the intensity (number of items/calculations) required for the project.

The exception, as mentioned above, is the "emergency register": a pseudo-register of sorts that operates a little differently. This is for all the small emergencies in life, the ones that are handled more by emotion, impulse, and reflex. For the purpose of planning, this can be ignored, as it is handled almost subconsciously (your mind's main employee is not the one that takes care of it, but rather a more automatic self-completion by the customers themselves). As this is not part of the main process, and is not carried out by the employee, this is not recommended for daily use, as critical errors by the unruly customers may occur, such as mis-charging themselves or damaging equipment. Depending on what occupation a person has, and how stressful a person's life, there may be varying numbers of emergency registers.

Another aspect that just came to mind is that the employee is always learning, from the moment you are born, and becomes more efficient over time. Eventually, he can build a new register to include more customers at once, but he does this from scratch (after all, such a poor-serviced company doesn't make much profit) and it can take many years. When you are born, you may have no registers and be forced to deal with everything all at once. After learning to build a register, customers learn to wait in line. Eventually, the employee learns to build another register and take care of two customers at once, greatly improving productivity by having the register machines automate the basic processes. Maybe by the teenage years, the mind-employee builds too many registers (e.g., 10 or 11), experiences diminishing returns due to overwork, and tears down the extra ones it cannot handle. It's a very dynamic process.

I was thinking about this because, as high school graduation comes up this Sunday (which is, coincidentally, also Father's Day) and I'm beginning to plan for the summer, I've begun to amass a great number of topics I want to learn, and prioritizing them is a problem for me now. For example, I wish to learn multivariable calculus and differential equations, the Lisp language (and the entire SICP textbook), Python, as well as consolidate my knowledge in various PHP and JavaScript technologies. Non-academically, I also want to blog, polish a few Studio Ghibli songs on the piano, and exercise. Put all together, this is a confusing glob of tasks, which I began to handle by randomly attacking a convenient task, and then becoming overwhelmed by the lack of structure. The thought of brain-spaces and registers came to me during a single shower, and its practical usage is in planning without becoming overwhelmed.

The planning process begins brain-spaces each task takes (again, arbitrarily defined and based both on the priority and complexity of the task). Next, the high-priority tasks are moved to fill the available mind-spaces. For example, because I want to finish multivariable calculus in a week, this will likely take three full mind-spaces for me. Then, half a brain-space will be given to SICP, review of programming knowledge in JS/PHP, piano, and exercise each, for a total of five brain spaces. Roughly speaking, each brain-space refers to one hour of focus on the given topic per day, for a total of five dedicated, intensely focus-able hours of the day. Once a task is complete (for example, after multivariable calculus clears out of my schedule in a week), those brain-spaces are freed up for new tasks from the queue to fill.

I didn't intend on spending so much time writing this post, or going so deep into a largely-theoretical and minimally-philosophical mental model I made for myself— but if you read all the way to here, and especially if it was some degree interesting or applicable to your own life, I applaud your effort.