On Developing a Linux Driver

By Jonathan Lam on 06/11/19

Tagged: veikk coding linux tutorial

Previous post: Diary of a College Kid

Next post: VEIKK Linux Driver v3 Notes

"Do you pine for the days when men were men and wrote their own device drivers?" ~ Linus Torvalds

On Developing a Linux Driver

A quick guide on understanding, developing, and compiling a Linux driver with no prior knowledge, featuring a case study. From someone who wrote a simple Linux driver in three days with no prior knowledge.

Update August 2020: This device is the first in a series documenting the development of the VEIKK Linux driver. The later blog posts are VEIKK Linux Driver v3 Notes and Button Mapping Journeys.

Background

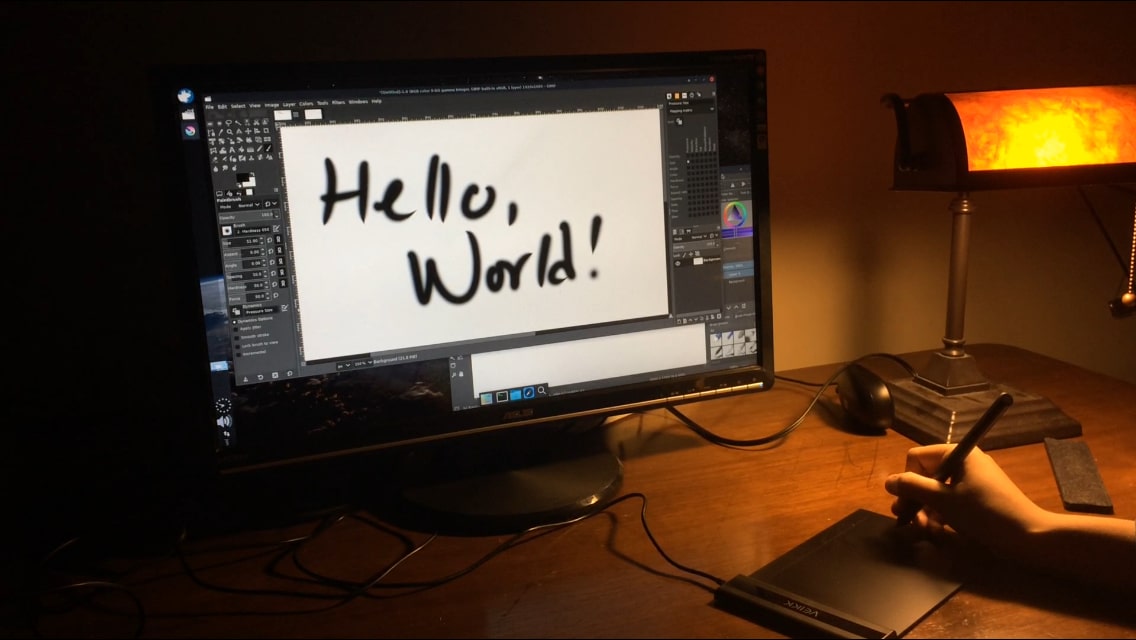

My sister really likes to draw. Our family got her a Veikk S640 pen tablet for her birthday last year. The problem is that most of the computers in our family run Linux, and the only drivers provided by Veikk are for Windows and Mac. On Linux, it is recognized as a mouse, so position and click are registered, but not pressure or the stylus buttons. So I revived an old Windows XP computer, installed the driver and a fun little piece of drawing freeware called FireAlpaca, and that was that.

Fast forward a year. I had just built my first computer out of old spare computer parts. Then I happened across this post on the Linux Stack Exchange, in which @tobiasBora found a way to make pressure sensitivity work on Linux. I tried his Python script, and it worked. It uses the uinput and libevdev libraries to create a new virtual device and to send out tablet events from that new virtual device, respectively.

Yay! Now I could use GIMP and Krita as drawing creation tools with this new pressure sensitivity.

@tobiasBora's post ended with:

Enjoy! (and I'll let you know if I write the C driver at some points)

Seeing that no driver had been written yet, I thought I might give it a shot.

Getting started with drivers: a brief conceptual understanding

This is not intended to be a full conceptual understanding, but a brief working understanding.

Users and user programs operate in the "user space," interacting with the user and with the kernel. They have no direct access to hardware devices, but can interact through the kernel interface for the hardware devices.

On the other hand, any code that is part of the Linux kernel is in the "kernel space," and provides a programming interface for user space applications. You can think of the kernel as the core of the Linux operating system (and it's on GitHub!).

To get a sense of the interface that user space applications have to work with, you can check out the /dev/ directory to see hardware devices. As we'll be dealing with input devices in this article, check out the /dev/input directory. Every file there represents an input device (since "files" in Linux don't always stick to the colloquial sense of the term), for which you can receive events (by reading the device) or push events or data to (by writing to the device).

To see some of this in action, try running evtest, choose an input device, and interact with that device. The events you're receiving are from that kernel-to-user-space file-like interface. Alternatively, you can run cat /dev/input/[device-name-here] to view input events as raw data.

But something needs to create these files, and handle user space actions like reading and writing to them. That's where the driver comes in. The driver creates this interface, mapping hardware actions (i.e., reading or writing raw data from some port) to the file-like interface. So when you open the device file for reading, you're actually calling the driver's read function, which can decide what to reutrn to you. Likewise, when you open, close, or write to the file, corresponding driver

functions are being called.

"Writing device drivers in Linux: A brief tutorial" was probably the most useful tutorial for this conceptual understanding. It does a very good job of explaining what it calls the user space and kernel space and the one-to-one mapping between the two. It explains each of the user operations very well and provides two full driver examples.

Writing a driver

Part 0: Writing a basic driver (without a hardware interface)

It's not hard to find a tutorial to start making drivers for Linux, but there didn't seem to be any that fit my needs of learning the basics and using the HID module. It took a lot of searching and rereading and copying and looking up and logging and debugging and blowing up a few Linux kernels to get it right.

To get started, Linux drivers are always written in C or Assembly code, so it'd be a good idea to learn one (most likely C).

If you read the tutorial "Writing device drivers in Linux: A brief tutorial," you'd see that a driver is called a "module" and written in C. (This modular design can then be loaded into the Linux kernel without recompiling the whole kernel, and is thus called a Loadable Kernel Module (LKM).) The basic view of the module looks like this:

// linux headers

#include <linux/kernel.h>

// ...

// module functions to implement for start/exit

static int mod_init(void);

static void mod_exit(void);

// kernel space functions to implement

int mod_open(struct inode *inode, struct file *filp);

int mod_release(struct inode *inode, struct file *filp);

ssize_t mod_read(struct inode *inode, size_t count, loff_t *f_pos);

ssize_t mod_write(struct inode *inode, size_t count, loff_t *f_pos);

// mapping from file operations (user space) to kernel space functions

struct file_operations mod_fops = {

read: mod_read,

write: mod_write,

open: mod_open,

release: mod_release

};

// functions run when starting/exiting the module

module_init(mod_init);

module_exit(mod_exit);

// module license (required)

MODULE_LICENSE("GPL");

(There are a lot of types here, which were not familiar to me as a non-kernel developer. If you're confused like I was, looking up device definitions on the Bootlin Elixir Cross Referencer for Linux was very helpful.)

You can see clearly the mapping of user space file operations to kernel space operations with the mod_fops variable. This mapping will be loaded in the creation of the driver in mod_init(), which should call register_chrdev(MODULE_MAJOR_NUMBER, MODULE_NAME, &mod_fops) to register the module as a device.

I.e.:

#define MODULE_MAJOR_NUMBER 60

#define MODULE_NAME "test-module"

static int mod_init(void) {

// ...

register_chrdev(MODULE_MAJOR_NUMBER, MODULE_NAME, &mod_fops);

// ...

}

module_init(mod_init);

As noted in the tutorial, you would have to create the /dev/module file manually for this simple driver to work, and it doesn't interface with a real hardware device

(but does show how to allocate and use kernel memory), but you can interface with the device file like you would any other driver.

Part 1: Writing a USB-interfacing driver

The conceptual tutorial above is great for very simple applications, but what if we wanted to write something a little more complex? While that may be great for your own hobby electronics gizmos, an example of a driver written with the usbhid module may be useful. There doesn't seem to be much documentation (or at least worked programming examples) on the module, so I hope this will be helpful to someone.

Driver development changes a little bit when a hardware device is used. Here we'll be dealing with a USB device, so some extra steps have to be taken, which are detailed well in this article.

Now, instead of register_chrdev() (which is used for a simple generic character device), a struct usb_driver object will need to be created, with the same file operations mapping, and new usb_mod_probe(), usb_mod_disconnect(), and usb_mod_id_table entities.

#define USB_MOD_NAME "usb-test-driver"

#define USB_VENDOR_ID 0x2feb

#define USB_PRODUCT1_ID 0x0001

#define USB_PRODUCT2_ID 0x0002

// same fops functions and mapping variable and module functions

// (except the init() function, see below) as previous example

// extra usb devices functions to implement

// called when device (matching usb_id_table) connect/disconnect

static int usb_mod_probe(struct usb_interface *intf, const struct usb_device_id *id);

static void usb_mod_disconnect(struct usb_interface *int);

// id table is a list of devices to match

// note that terminating entry must be empty

static struct usb_device_id usb_id_table[] = {

{ USB_DEVICE(USB_VENDOR_ID, USB_PRODUCT1_ID) },

{ USB_DEVICE(USB_VENDOR_ID, USB_PRODUCT2_ID) },

// ... etc.

{ } // terminating entry

};

// for hotplugging scripts

MODULE_DEVICE_TABLE(usb, usb_id_table);

// data for registering usb device driver

static struct usb_driver usb_driver {

.name = USB_MOD_NAME,

.probe = usb_mod_probe,

.disconnect = usb_mod_disconnect,

.fops = &usb_mod_fops,

.id_table = usb_mod_id_table

};

// driver init function

static int usb_mod_init(void) {

// ...

usb_register(&usb_driver);

// ...

}

module_init(usb_mod_init);

There are a few extra parts here. First, usb_id_table is an array of objects created using the USB_DEVICE macro; when a device matching any entry from the ID table is matched, the usb_mod_probe() function is called. If usb_mod_probe() returns 0, then the driver is attached to the device. Similarly, usb_mod_disconnect() is called when a device disconnects from the driver.

The ID table is an array of struct usb_device_id (with a null terminating entry). Each struct usb_device_id (except for the null entry) is used to match one or more hardware devices; the USB_DEVICE(vendorId, productId) macro defaults to matching a specific device by vendor and product ID. I used this in my driver, as I was matching a very specific product (Veikk's vendor ID is 0x2feb, and the Veikk S640 has product ID 0x0001.)

Lastly, note the MODULE_DEVICE_TABLE macro: this registers the ID table for hotplugging, so that when a device matching the ID table is plugged into the computer, this driver will get loaded automatically.

Part 2: Working with usbhid for HID devices

If you're not planning to work with HID devices fitting the input protocol, you can totally ignore this. But if you are, this should be helpful because I could not seem to find explanatory examples of this. But be warned that this was all learnt by inference looking over Wacom's driver, and may not be totally complete.

I read over the tutorials and reference pages that are linked above, along with many others, but I still didn't know where to start. I didn't particularly want to deal with pure raw data and the fops objects, primarily because there are standards for what events should look like (e.g., pen pressure, position, and button presses), so that programs can uniformly interpret them as according to some specification. (I'm not really sure what the specification is called, but I'll refer to it as

the HID specification.) In other words, the data being read from the device files should follow some uniform interface, and I didn't want to implement it from scratch.

I began to look for examples. (Quick flash of false hope: Hawku's TabletDriver includes the Veikk S640! But it's for the Windows/MacOS game osu!) Then I peeked around Linux and found out that there was a directory of HID drivers. In the end, I looked heavily at the files in the usbhid subdirectory (the usbhid directory) and the Wacom files (wacom-sys.c, wacom-wac.c, wacom-wac.h). By inspection, it looks as though the wacom-sys.c had more of the core module files, and the wacom-wac.c file had more of the customization details for all of its devices. Because I was working only with a single tablet, the Veikk S640, I decided to not worry about much of wacom-wac.c until I had to get to it. Of course, many useful definitions were in wacom-wac.h, as well as in linux/hid.h, and linux/usb/input.h. Again, if any symbol is unclear, I highly recommend looking up its source and definition in the Bootlin Elixir Cross Referencer for Linux, which proved very useful for me.

How I went about it was starting from the basics: creating a module. Like the upgrade from a generic character device to a USB driver, the upgrade from a USB driver to using the usbhid library changes the syntax slightly. The struct usb_driver is now replaced with a (very similar) struct hid_driver, and then a macro is defined to set up this driver, replacing the module_init() and module_exit() functions. So this part is actually shorter than before.

static struct hid_driver veikk_driver = {

.name = "veikk",

.id_table = id_table,

.probe = veikk_probe,

.remove = veikk_remove,

.raw_event = veikk_raw_event

};

module_hid_driver(veikk_driver);

Next was to implement the ID table. Again, this is similar to the USB driver. The vendor and device ID was found with the lsusb command.

static const struct hid_device_id id_table[] = {

// Veikk's vendor ID is 0x2feb

// S640's product ID is 0x0001

{ HID_USB_DEVICE(0x2feb, 0x0001) },

{ }

};

MODULE_DEVICE_TABLE(hid, id_table);

The next step was to implement the veikk_probe() and veikk_remove() methods. I thought this was going to be brief, but that was not the case! After this was done, however, then I could check if the driver was loaded when the device was present. The rest of the steps was heavily reliant on Wacom's code, since I could not find a tutorial on using the usbhid driver.

There are two important structs to discuss before continuing. Wacom created a struct wacom to hold hardware interface data, and a struct wacom_wac to hold user interface data (i.e., the struct input_devs that will write to the driver device file). (I'm not actually sure what the _wac in wacom_wac stands for, but I went ahead and named my own struct veikk and struct veikk_vei.) Organizationally, there is one struct veikk and struct veikk_vei for each device, so they could have been combined into a single struct, but I stuck to Wacom's convention. Here are their definitions:

// struct for user interface

struct veikk_vei {

struct input_dev *pen_input;

struct input_dev *touch_input;

struct input_dev *pad_input;

unsigned char data[VEIKK_PKGLEN_MAX];

};

// struct for hardware interface

struct veikk {

struct usb_device *usbdev;

struct usb_interface *intf;

struct veikk_vei veikk_vei;

struct hid_device *hdev;

};

The probe function is passed the hid_device struct and the hid_device_id (from the device table, and thus device information can be obtained from here. Because this driver was only for one device, I didn't use this ability). Here's a summary of the veikk_probe() (and all functions called by it).

- Allocate an empty

struct veikkin the kernel (usingdevm_kzalloc()), populate it with the hardware device and interface details, and add it to the HID device struct (devices have an arbitrary data memberdriver_datathat can be populated usinghid_set_drvdata()). hid_parse()to parse a report description of the device and populate fields of the HID device struct (necessary forhid_hw_start()).- Allocate a

struct input_devassociated with the Veikk's pen usingdevm_input_allocate_device(). This will manage writing the events to the user later. - Set up the input capabilities of the pen:

- Set the

EV_KEYandEV_ABSevent bits. - Set the

INPUT_PROP_POINTERproperty bit. - Set the

BTN_TOUCH,BTN_STYLUS, andBTN_STYLUS2key bits. - Set the parameters of the

EV_ABSinputs (minimum, maxmimum, and resolution for X, Y, and pressure)

- Set the

hid_hw_start()to start HID device.

The veikk_remove() function performs these tasks:

hid_hw_stop()to remove the device.- Set driver data to NULL using

hid_set_drvdata().

When I compiled the driver, I encountered another problem: hid-generic, the default hid-device, was taking the device before my driver, even though a comment in its driver states that "If any other driver wants the device, leave the device to this other driver." Note that only one driver can bind to any hardware device, and that hid-generic also detects the Veikk tablet (remember, it identifies it as a mouse). I found a way to unbind a driver, and by doing this I was able to successfully bind the tablet to my driver.

sudo su

echo -n "0003:2FEB:0001.xxxx" > /sys/bus/hid/drivers/hid-generic/unbind

where 0003 and xxxx are the major and minor numbers of the tablet, respectively. Along this same vein of thought, you can see which devices are attached to a driver because they are listed in the driver's directory (e.g., /sys/bus/hid/drivers/hid-generic for hid-generic or /sys/bus/hid/drivers/veikk for my driver) as directories. Similarly, the devices (e.g., in /sys/bus/hid/devices/) are directories with a driver subdirectory that link to their attached driver. I found this interwoven link between driver and device pretty fascinating. (It also makes for fun /[DEVICE]/driver/[DEVICE]/driver/[DEVICE]/driver/ directory recursion.)

I was compiling this on kernel 4.15 when I had this error, but when I ran this on 4.18 and 5.1 kernels, this hotplugging issue never appeared and the driver worked perfectly. There was an update to the automatic unbinding of hid-generic affecting 4.17 and later that may have caused this, but I'm not sure. I'll reinstall these older kernels and do more testing in the future.

The next step was to actually parse the data coming in. Now that everything was set up, this part was relatively easy (and fun!). This involves implementing the veikk_raw_event() function. The function is handed a pointer to raw data, and the length of the data. The S640 returned uniform 8-byte packets.

- Parse raw data* for pressure, x and y coordinates, button presses.

- Report these data using

input_report_key()(for button presses) andimport_report_abs()(for position and pressure).

The Wacom driver had many different device-dependent parsing functions. I decided that I wanted to do this step for myself rather than take any influence from Wacom's driver. By virtue of logging and experimenting with the pen, here's what the 64 bits seemed to signify.

- Byte 0: The constant value 1. Most likely the product ID.

- Byte 1: First five bits 0, last three bits 0.

- Bit 5 indicates if stylus button 2 is being pressed.

- Bit 6 indicates if stylus button 1 is being pressed.

- Bit 7 indicates if the pen is touching the pad.

- Byte 2: All variable. The last 8 bits of the X position.

- Byte 3: First bit 0, last seven bits variable. The first 7 bits of the X position.

- Byte 4: All variable. The last 8 bits of the Y position.

- Byte 5: First bit 0, last seven bits variable. The first 7 bits of the Y position.

- Byte 6: All variable. The last 8 bits of the pressure.

- Byte 7: First three bits 0, last five bits variable. The first 5 bits of the pressure.

These observations were very satisfactory, because the Veikk S640 is reported to have 32768x32768 (2^15x2^15) position resolution and 8192 (2^13) pressure levels. And look! 15 bits for position in either dimension, and 13 for pressure.

These can be written concisely as:

// buttons

int btn_touch = data[1] & 0x01;

int btn_stylus = data[1] & 0x02;

int btn_stylus2 = data[1] & 0x04;

// absolute readings

int abs_x = (data[3] << 8) | (unsigned char) data[2];

int abs_y = (data[5] << 8) | (unsigned char) data[4];

int abs_pressure = (data[7] << 8) | (unsigned char) data[6];

Peeking at the Wacom data parsing, it looks like there's a method in asm/unaligned to do exactly the latter operation: get_unaligned_le16(), so the absolute readings can be simplified:

// absolute readings

int abs_x = get_unaligned_le16(&data[2]);

int abs_y = get_unaligned_le16(&data[4]);

int abs_pressure = get_unaligned_le16(&data[6]);

And that was that! This sent in the data beautifully, and the driver works: pressure sensitivity and the buttons work well and have their intended use in drawing programs (e.g., GIMP and Krita). You can see the whole Veikk driver on GitHub. Currently, it is under 300 lines, much slimmed down compared to the 8000 lines for the Wacom driver.

Debugging the driver

This is short, but I wanted to make this its own section so it'd stand out.

While I'm not terribly sure how to debug using standard debugging tools since this runs in kernel space, it is easy to log outputs.

But where? It's not attached to some terminal when it is run by the kernel.

It turns out, kernel drivers may use the printk() function, whose output is logged to dmesg (driver message). Running dmesg -w to watch the output makes it feel just like any console logging output. This was useful when reverse-engineering the raw data input.

Driver compilation

This is easy to look up, but most sources do not provide an explanation of the steps. To see if your module (driver) is installed, run lsmod | grep MODULE_NAME (e.g., lsmod | grep veikk). Play around with lsmod (list modules); to see more details about any module, use modinfo MODULE_NAME. (Replace MODULE_NAME in all of the following snippets with your module name)

You can load your module two different ways: "temporarily" or "permanently" (installation). The difference is that a temporary driver is not loaded from /lib/modules/$(uname -r)/modules.dep, while a permanent one is. (Note that this is not a technical definition, but just an easy designation, and are fundamentally the same.) The former method is simpler and quicker than the latter.

Note that in all of the below examples, uname -r refers to the current kernel version, and $(uname -r) is a command substitution (i.e., will be replaced with a string literal of your current kernel version).

Pay attention to the NOTE below.

If you don't want to read these subsections and just want compilation and installation to work, check out the "Completed Makefile" section below for the finished product. The rest is just explanation.

Compiling the driver

Make (haha?) sure you have make installed on your system (package build-essentials), as well as the linux headers (in Ubuntu, this lies in the linux-headers-$(uname -r); in Arch, this lies in the linux-headers package). The symptom of the latter is that the /lib/modules/$(uname -r)/build directory will be missing.

Write the following into your Makefile:

obj-m := MODULE_NAME.o

To compile, use the following command:

make -C /lib/modules/$(uname -r)/build M=$(CURDIR) modules

Here's a quick breakdown of the command:

make modules // run the `modules` target (from the kernel Makefil)

-C /lib/modules/$(uname -r)/build // look at the Makefile in this directory

M=$(CURDIR) // look at the current directory for source files

In short, the make command tells make to look at the Makefile in the /lib/modules/$(uname -r)/build directory, and run its modules target on the files in the current directory.

NOTE: Take note of the use of $(CURDIR) instead of $(PWD) ($(shell pwd) or $(pwd) are also possible alternatives, but $(CURDIR) is to be preferred). See this, this, this. In tutorials about compiling the Linux module, I've only seen $(PWD) (e.g., this, this, this). While $(PWD) seemed to be set for make on my system, it was not when running sudo make install (or any sudo command); this cleared the /lib/modules/$(uname -r)/kernel directory, where almost all the drivers are stored, wiping all of my drivers (except for the one I just made, since it gets installed in /lib/modules/$(uname -r)/extra). I'm not entirely sure why this happens, but it happened on kernel versions 4.15.0-20-lowlatency, 4.15.0-51-lowlatency, and 4.15.0-51-generic, and was a problem I didn't know how to fix. Luckily I had other kernel versions to switch to when the previous one broke (thanks Ukuu!), and the problem was diagnosed and a solution found after only messing up three kernels. I don't know if my system is abnormal or if the abundance of tutorials online are outdated, but I'd say it can't hurt to switch to $(CURDIR).

Temporary driver loading/Loading from files: insmod and rmmod

After compiling the driver, run insmod MODULE_NAME.ko to load it. Pretty self-explanatory. When you run lsmod, you should now see your driver pop up, and you can try out your driver. Hurrah!

To unload it, you can run rmmod MODULE_NAME. Note that there is no .ko, because rmmod takes a module name as an input, not a driver file.

Since this temporary loading does not save your file to the /lib/modules/$(uname -r) directory (and therefore the driver is not in /lib/modules/$(uname -r)/modules.dep), the module will not be "saved" onto your computer and will not persist when rebooting.

Permanent driver loading (install): modprobe (and depmod)

("Permanent" in the sense that it is not temporary, and will remain on your system on boot, but it can still be unloaded.)

This involves the make modules_install command, which compiles the module and saves it to the /lib/modules/$(uname -r)/extra directory. The format of the command is similar to the compilation, but instead uses the modules_install target. Make sure you have already run the make modules (compilation) command.

make -C /lib/modules/$(uname -r)/build M=$(CURDIR) modules_install

Now the driver is installed within /lib/modules/$(uname -r), but it still has to be loaded. There are two more commands that will come in handy here: depmod and modprobe. depmod scans the /lib/modules/$(uname -r) directory and its subdirectories for drivers, and updates the /lib/modules/$(uname -r)/modules.dep file. modprobe is used to load or unload modules found by depmod (i.e., installed modules). Thus:

depmod

modprobe MODULE_NAME

Permanent driver unloading (uninstall): modprobe -r (and depmod)

Unload the driver, remove it from the /lib/modules/$(uname -r) directory, and run depmod to reload modules. The meaning and order of the following commands should be pretty clear; the only thing to note is the wildcard at the end of the filename. This is because it seems some newer kernels compress their .ko files, leading to .ko.xz files.

modprobe -r MODULE_NAME

rm /lib/modules/$(uname -r)/extra/MODULE_NAME.ko*

depmod

Final Makefile (with compilation and driver install/uninstall)

The final Makefile for the Veikk driver looks like this (and can be adapted for a similar driver just by changing the module name):

MOD_NAME := veikk

BUILD_DIR := /lib/modules/$(shell uname -r)

obj-m := $(MOD_NAME).o

all:

make -C $(BUILD_DIR)/build M=$(CURDIR) modules

clean:

make -C $(BUILD_DIR)/build M=$(CURDIR) clean

install:

make -C $(BUILD_DIR)/build M=$(CURDIR) modules_install

depmod

modprobe veikk

uninstall:

modprobe -r $(MOD_NAME)

rm $(BUILD_DIR)/extra/$(MOD_NAME).ko*

depmod

The installation instructions for this driver are:

make

sudo make install clean

and the uninstall instructions are:

sudo make uninstall

Conclusion

So it turns out that I had to leave home right after finishing writing a working driver (my train left 20 minutes later), so I didn't get around to a lot of additional tweaking, testing, and tidying up. Until I get back home, the code may remain a bit messy and have some parts I unnecessarily took from Wacom. But it works, and I'm pretty proud of getting it to work, even if it is such a short script (when writing this article and distilling down the steps, how much I accomplished seems almost trivial) and if I completely ripped much of it off of Wacom's open source driver.

There's still much to do, however -- I'd like to implement drivers for all of Veikk's drawing tablets, as well as a configuration utility. There's also cleanup to do, signing the module, and fixing the hid-generic bug; I've been talking with an S640 user who had trouble installing this driver because of the signed module and because of hid-generic.

This was a fun effort that consumed my weekend (and the past few hours writing this). I really think it paid off with how much I learnt about the Linux kernel and drivers, and I think it'll keep paying off as I continue to expand on this driver. I hope this might others started writing drivers as well!